The Wisdom Behind the Words

Have you ever met someone who nods along with everything you say, only to trash-talk you the moment you leave the room? Or perhaps you’ve experienced the opposite—someone who openly disagrees with you but treats you with genuine respect?

This contrast is precisely what Confucius was getting at with one of his most insightful observations:

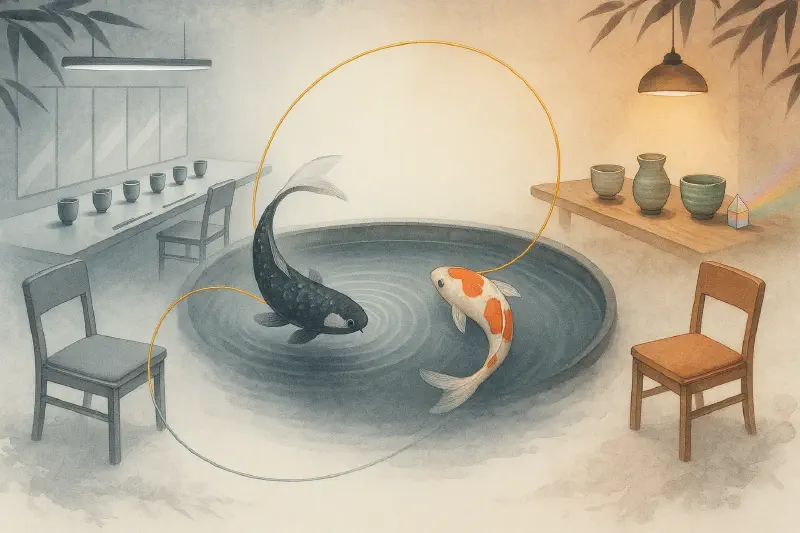

“君子和而不同 小人同而不和。”

(Jūnzǐ hé ér bù tóng, xiǎorén tóng ér bù hé.)

Which roughly translates to:

“The superior person is harmonious but not conforming; the petty person conforms but is not harmonious.”

But before we dive into unpacking this wisdom, let’s take a step back.

Confucius: Not a Sage on a Mountain, Just Your Philosophical Grandpa

When we encounter ancient wisdom, there’s a tendency to imagine these philosophers as mystical beings dispensing perfect truths from mountain tops. But that mental image doesn’t do us any favors.

Confucius was essentially a thoughtful older man trying to guide his students through life’s complexities. Like your grandparent sharing lessons over dinner, he tailored his teachings to specific people in specific situations.

This means two important things:

- His words were never meant to capture the entirety of his thought (no words ever could)

- The context of his teaching matters as much as the words themselves

So when approaching this quote, I try to imagine Confucius noticing a pattern in human relationships and trying to articulate it in a way his students could grasp and remember.

The Dinner Party Example: A Tale of Two Tables

Let me illustrate this concept with a modern scenario:

Table One: The Echo Chamber

Alex hosts a dinner party and invites only friends who share identical political views. Throughout the evening, everyone eagerly agrees with each other’s statements:

“The tax policy should absolutely be reformed!” “Yes, exactly what I was thinking!” “I couldn’t agree more!”

The conversation flows smoothly with constant agreement. Yet afterward, several guests text each other:

“Did you hear how Alex dominated the conversation? So annoying.” “And that comment about the economy? Completely simplistic.”

Despite their surface agreement, there’s no genuine harmony or respect.

Table Two: The Respectful Debate

Meanwhile, at Jordan’s dinner party across town, the guests hold diverse perspectives. When the conversation turns to climate policy, there’s visible disagreement:

“I believe government regulation is the only path forward.” “Actually, I think market-based solutions would be more effective.” “I see valid points in both approaches, though I lean toward community-based initiatives.”

The discussion involves disagreement, occasional tension, and thoughtful exchanges. When the night ends, guests leave thinking:

“I still don’t agree with Maya’s position, but she raised points I hadn’t considered.” “Jordan creates a space where we can disagree without it feeling personal.”

Despite their differences, there’s genuine harmony and mutual respect.

The Spectrum of Character: Breaking Down the Quote

Let’s break down what Confucius meant by each part of this saying:

“The superior person is harmonious but not conforming”

The term “superior person” (君子, jūnzǐ) doesn’t mean someone inherently better than others—it refers to someone striving for self-improvement and ethical behavior. In modern terms, think of it as “someone working on personal growth.”

Such a person:

- Seeks harmony in relationships without requiring agreement

- Values the relationship itself above winning arguments

- Can maintain respect for someone despite intellectual disagreements

- Sees different perspectives as opportunities to learn, not threats

- Prioritizes understanding over converting others

“The petty person conforms but is not harmonious”

Conversely, the “petty person” (小人, xiǎorén) describes someone focused on self-interest rather than growth. Again, this isn’t a permanent label but a description of behavior.

This behavior pattern includes:

- Outwardly agreeing while internally rejecting others’ views

- Using surface agreement as a social tool without genuine respect

- Prioritizing appearances over authentic connection

- Seeing relationships as transactional rather than meaningful

- Feeling threatened by differences rather than enriched

Beyond Black and White: The Reality of Human Nature

Here’s where we need to recognize something Confucius implied but didn’t explicitly state: nobody is entirely a “superior person” or a “petty person” all the time.

Think of these categories as ends of a spectrum rather than binary labels. We all move along this continuum depending on:

- Who we’re interacting with

- Our emotional state

- The context of the situation

- Our personal growth journey

- The stakes involved

Even Confucius himself wouldn’t claim to perfectly embody the “superior person” ideal at all times. The point isn’t to achieve perfection but to recognize the direction worth moving toward.

The Modern Workplace: Where This Wisdom Shines

I’ve found this concept particularly valuable in professional settings. Here’s a real scenario from my experience:

During a product development meeting, our team was split on the direction for a new feature. Mei, our UX designer, advocated for a streamlined approach focusing on core functionality. Diego, our marketing lead, pushed for additional elements he believed would attract new users.

Their approaches fundamentally conflicted, and neither would fully get their way. But how they handled this conflict revealed volumes about their characters:

Diego’s Approach (Harmony without Conformity): “I see why you’re prioritizing simplicity, Mei. User experience is crucial. I still believe we need these marketing elements, but maybe we can find a compromise that preserves the clean interface while incorporating some key promotional components.”

Contrast with a Colleague’s Reaction (Conformity without Harmony): “Sure, whatever you think is best, Mei.” [Later in a separate Slack channel] “Can you believe how stubborn the UX team is being? They never consider the business impact of their precious ‘clean designs’.”

The difference wasn’t in whether they agreed—it was in how they maintained respect while disagreeing.

Practical Steps Toward Being the “Superior Person”

So how do we move toward the “harmony without conformity” end of the spectrum? Here are some practices I’ve found helpful:

- Separate ideas from identity - Challenge someone’s view without challenging their worth

- Practice intellectual humility - Approach disagreements assuming you might learn something new

- Seek understanding before agreement - Ask questions that help you truly grasp the other’s perspective

- Voice disagreement respectfully - Frame differences as alternative perspectives rather than corrections

- Look for partial truths - Acknowledge the valid aspects of viewpoints you mostly disagree with

- Express appreciation - Thank others for sharing perspectives that differ from yours

The Hardest Test: Political and Moral Disagreements

The most challenging application of this wisdom comes with deeply held beliefs about politics, religion, or ethics. Consider this example:

Thomas and Jack regularly meet for coffee despite fundamentally different views on criminal justice. Thomas believes the death penalty should be abolished on moral grounds, while Jack supports it in certain cases.

After years of conversation, neither has converted the other. Yet they continue their friendship because:

- They recognize each other’s position comes from genuine moral reasoning, not malice

- They’ve learned to separate their respect for each other from agreement with each other’s views

- They value how these discussions have deepened their own thinking

- They prioritize their human connection above ideological conformity

When Thomas sees Jack across town, he thinks, “There’s my friend with whom I profoundly disagree—and whom I deeply respect.”

The Daily Practice of Harmony

Ultimately, Confucius wasn’t giving us an unattainable ideal but a practical approach to daily life. We can practice this wisdom in small ways:

- With family members whose political views make us cringe

- With colleagues whose work approach differs fundamentally from ours

- With neighbors whose lifestyles we don’t understand or share

- With ourselves when we notice our own tendency to either force agreement or withhold respect

The practice isn’t about achieving perfect harmony or becoming the perfect “superior person.” It’s about moving incrementally toward valuing both honesty and respect, toward creating relationships where differences don’t diminish connection.

As Confucius might tell us if he were sharing wisdom over coffee today: The goal isn’t perfection but direction—moving toward being the kind of person who can disagree openly while respecting deeply.

Daily Confucius

View all 5 posts in this series

- 1. True Harmony: Embracing Differences While Maintaining Respect (current)

- 2. When Visions Collide: Why Shared Goals Are Essential for Collaboration

- 3. Within the Four Seas: Finding Brothers Everywhere

- 4. Beyond Intelligence: Confucius on Social Harmony and Hidden Meanings

- 5. The Hidden Balance: What Confucius Really Meant by Inner Character vs Outward Cultivation