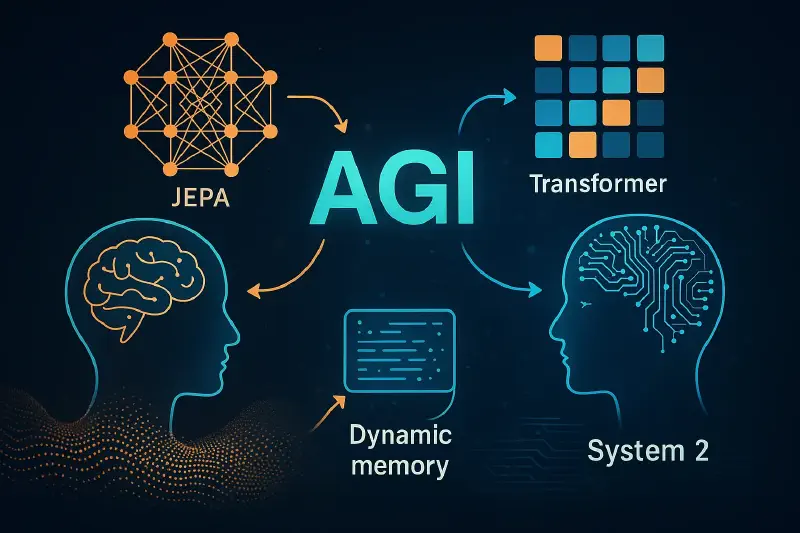

The recent NVIDIA GTC 2025 session titled “Frontiers of AI and Computing,” featuring AI pioneers Yann LeCun and Bill Dally, sparked my latest journey into exploring the future of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI). The conversation delved into emerging trends in deep learning, the evolution of AI architectures, and the crucial role of innovative hardware. Inspired by this, I found myself revisiting a fundamental cognitive framework: Daniel Kahneman’s famous “System 1” and “System 2.”

Moving Beyond System 1 vs. System 2

Kahneman categorizes human thought into two distinct modes:

- System 1: Fast, automatic, and intuitive.

- System 2: Slow, deliberate, and analytical.

However, the more I pondered, the clearer it became that our thinking doesn’t neatly fit into these two boxes. Instead, it exists on a continuum—imagine it as a smooth gradient rather than a binary toggle switch. At the low end, we have purely subconscious, reflexive processes, and at the high end, deeply reflective, philosophical considerations. This insight led me to think: why shouldn’t our AI models mirror this continuous spectrum as well?

Visualizing Abstract Thinking with JEPA

To better understand this gradient, consider how we visualize complex objects. Humans effortlessly transform raw sensory data—two slightly different images from our eyes—into a vivid three-dimensional mental image. We then abstract meaningful details from this mental model, passing these insights upward into more deliberate, analytical thought processes.

This realization led me to JEPA (Joint Embedding Predictive Architecture), introduced by Yann LeCun. JEPA inherently models predictive cognition, much like our intuitive “System 1.” It predicts missing information in a manner closely resembling human intuition. Initially, integrating JEPA with transformer models like GPT seemed natural. Transformers, though excellent at generating coherent language step-by-step, lack JEPA’s predictive abstraction. Could integrating these two provide a richer cognitive architecture?

Integrated Attention: Combining Transformers and JEPA

But how to integrate these models practically? Rather than treating JEPA and transformers as parallel streams, imagine embedding JEPA directly into the transformer’s latent space. Consider attention mechanisms as the “gatekeepers” of information, dynamically deciding:

- When to utilize JEPA’s predictive insights (think of JEPA as intuitive “gut feelings”).

- When to rely purely on the transformer’s detailed, token-by-token generation.

This idea can be visualized as a mental switchboard, continually adjusting the balance between quick intuition and meticulous logic based on context. Such dynamic flexibility resembles how humans effortlessly shift between quick judgments and careful analysis.

Snapshot Learning: Capturing Knowledge Over Time

Continuing my exploration, I imagined a scenario akin to human memory—learning through snapshots. Instead of endlessly fine-tuning one enormous model, we could capture discrete “snapshots” of knowledge after intervals (e.g., after every 10 million training tokens). Each snapshot adds a new, lightweight layer, akin to LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation), stacked upon previous layers.

This approach offers a clear analogy: imagine layers of sediment in geology, each representing knowledge acquired at a certain time. Older layers gradually become less relevant and eventually get compressed or discarded, maintaining efficiency.

Expanding Dimensions for Dynamic Knowledge Management

I took this concept a step further by suggesting a third dimension in latent space—essentially stacking layers vertically. Each training session would add a new “knowledge” layer along this dimension. When the model makes predictions, it aggregates these layers by summing along this new axis, combining historical insights into cohesive understanding.

Yet, this raised an important concern: increased dimensionality means significantly larger model size, a potential computational nightmare. My solution? Regular pruning or consolidation steps, merging older, less useful layers into compact forms, thus balancing knowledge retention and efficiency.

Addressing Model Uncertainty

I also thought deeply about uncertainty—an inherent human trait. Currently, language models stubbornly produce answers even when uncertain. Instead, why not explicitly encode uncertainty? Imagine training models to output a special token (“I’m not sure”) whenever uncertainty arises. This token would cue the model to pause and possibly re-engage JEPA’s broader, predictive context, much like a human stepping back to reconsider.

Dynamic Forgetting and Continuous Learning

My final insight centered around dynamically managing knowledge, emulating human memory’s flexibility. Humans naturally prune obsolete information. AI models, currently, do not. Could we implement a “negative LoRA” mechanism—actively pruning obsolete parameters?

This approach parallels “elastic weight consolidation,” where critical parameters remain fixed while less useful parameters get pruned or updated. Regularly evaluating knowledge relevance ensures that models remain both up-to-date and computationally manageable.

Final Thoughts and Open Questions

Reflecting on this exploration, my conclusion is clear:

- We shouldn’t isolate System 1 and System 2; we need a unified, integrated cognitive system, seamlessly blending intuitive and analytical processing.

- We need dynamic mechanisms to continually learn and selectively forget, mirroring natural cognitive flexibility.

Yet, questions remain:

- How can we manage the computational complexity introduced by multi-dimensional latent spaces?

- Will dynamic pruning realistically keep models efficient?

- Can integrated attention truly simulate seamless shifts between intuitive and analytical modes?

These questions will guide my future exploration. Ultimately, understanding and mimicking human cognition demands we go beyond traditional dichotomies, instead embracing a fluid, dynamic interplay—a direction I am eager to pursue further.